When Does Halley's Comet Return? 2061 Guide, History & How It Compares to 3I/ATLAS

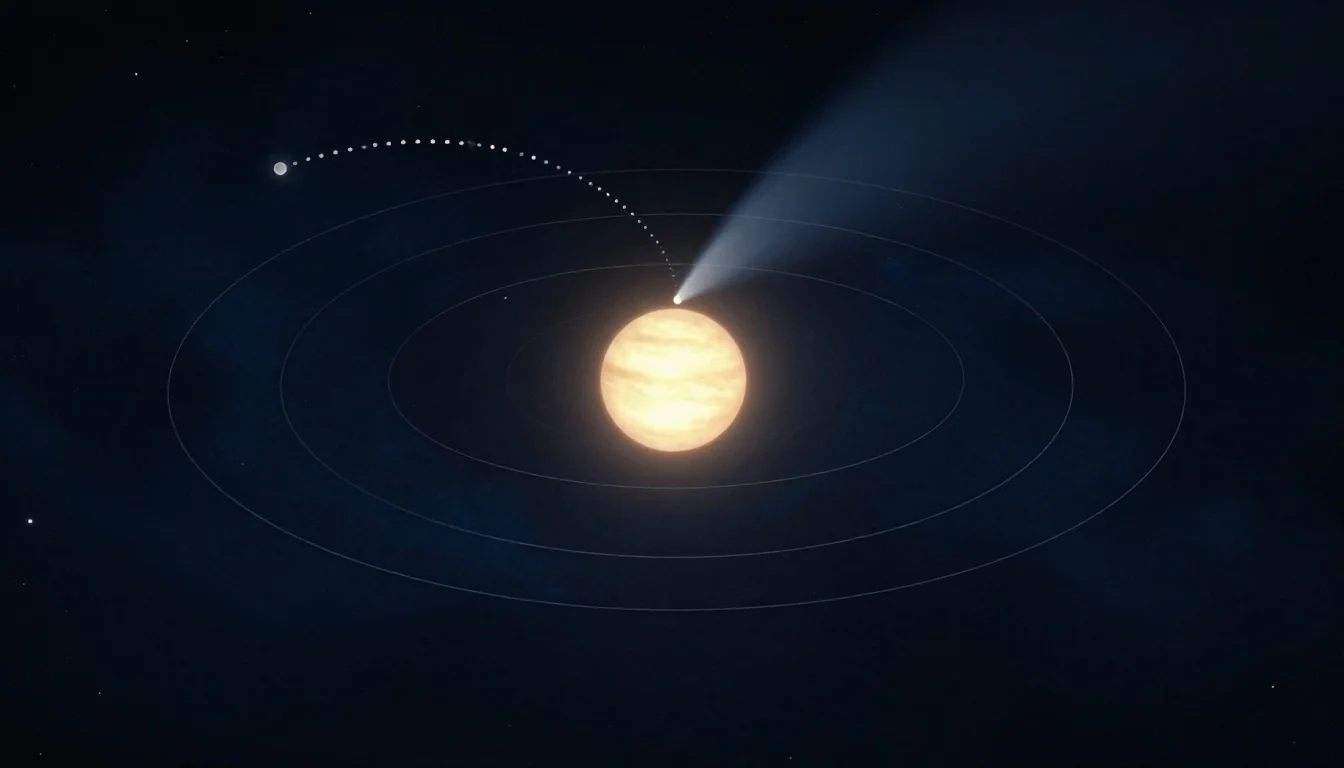

Halley's Comet — the most famous comet in human history — is coming back. Its next perihelion falls on July 28, 2061, and this time the geometry is spectacular: the comet will be roughly 10 times brighter than its disappointing 1986 appearance, visible to the naked eye for weeks, with a tail stretching up to 15 degrees across the sky.

But where is Halley right now? What happened during its last visit? And how does the solar system's most celebrated periodic comet compare to 3I/ATLAS, the interstellar visitor that just passed through our neighborhood? Here is everything you need to know.

When Does Halley's Comet Return?

Halley's Comet reaches perihelion on July 28, 2061, passing within 0.587 AU (87.8 million km) of the Sun — inside Venus's orbit. One day later, on July 29, 2061, it makes its closest approach to Earth at 0.477 AU (71 million km).

This is dramatically better geometry than 1986, when the comet and Earth were on opposite sides of the Sun. In 2061, they'll be on the same side, making for a far superior show.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Next perihelion | July 28, 2061 |

| Closest to Earth | July 29, 2061 (0.477 AU) |

| Orbital period | ~76 years |

| Last perihelion | February 9, 1986 |

| Predicted peak brightness | magnitude -0.3 (brighter than Vega) |

The best viewing window will run from May through September 2061. The likely pinnacle comes around August 4-8, when the comet's head should glow at approximately first magnitude with a fully developed tail spanning 10-15 degrees — roughly the width of your fist held at arm's length.

Where Is Halley's Comet Right Now?

In February 2026, Halley's Comet sits in the constellation Hydra, approximately 35 AU from the Sun — beyond the orbit of Neptune, near Pluto's distance. It reached aphelion on December 9, 2023, at a distance of 35.14 AU (5.27 billion km), and has just barely begun its 37.6-year inbound journey.

At this distance, the comet is essentially a frozen, inert lump of ice and rock. Its current brightness is approximately magnitude +35 — roughly 100 billion times fainter than the faintest star visible to the naked eye. The last confirmed observation was by the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in 2003, when Halley was at magnitude +28.2 and 28.1 AU from the Sun. No telescope on Earth or in space can currently detect it.

At aphelion, Halley crawls along at just 0.91 km/s (2,000 mph) — barely moving compared to its blazing 54.55 km/s (122,000 mph) at perihelion. That's a 60:1 speed ratio between its fastest and slowest points, a dramatic consequence of Kepler's second law and its extreme orbital eccentricity of 0.967.

The comet won't become detectable again until the early-to-mid 2050s, when it falls inside Jupiter's orbit and solar heating begins to sublimate its surface ices.

2,000 Years of History

Halley's Comet has been recorded by human civilizations for over two millennia. Here are the defining moments:

240 BC — First confirmed record. Chinese astronomers documented it in the Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian): "A broom star first appeared in the east, then it appeared in the north." This is the earliest observation that can be confidently linked to Halley through orbital back-calculations.

1066 — The Bayeux Tapestry. Halley appeared in April 1066, months before the Battle of Hastings. The Bayeux Tapestry depicts it in Scene 32 with the Latin inscription "Isti mirant stellam" ("These men wonder at the star"). Harold II died at Hastings; William the Conqueror took the throne. It remains the first known pictorial depiction of the comet.

1301 — Giotto's Star of Bethlehem. Italian painter Giotto di Bondone saw Halley in 1301 and painted it as the Star of Bethlehem in his fresco Adoration of the Magi in the Scrovegni Chapel, Padua. Six centuries later, ESA named their Halley spacecraft after him.

1705 — Edmond Halley's prediction. Using Newton's gravitational theory, Halley calculated that the comets of 1531, 1607, and 1682 were the same object. He predicted its return in 1758. He died in 1742, but the comet arrived on Christmas Day 1758 — confirming both his prediction and Newtonian physics.

1835 — Mark Twain's birth. Samuel Clemens was born on November 30, 1835, two weeks after Halley's perihelion. In 1909, he wrote: "I came in with Halley's comet in 1835. It is coming again next year, and I expect to go out with it." He died on April 21, 1910, one day after perihelion — exactly as he predicted.

The 1910 Cyanogen Panic

The 1910 return produced one of the most remarkable episodes of mass hysteria in modern history.

French astronomer Camille Flammarion announced that spectroscopic analysis had detected cyanogen — a toxic gas — in Halley's tail. Since Earth would pass through the tail on May 20, 1910, he speculated it could "impregnate the atmosphere and possibly snuff out all life on the planet."

The resulting panic was extraordinary:

- "Anti-comet pills" were sold for $1 each, promising to neutralize the poison

- Gas masks became bestsellers in major cities

- "Comet-protecting umbrellas" were marketed to frightened citizens

- Bartenders claimed whiskey and scotch would protect against cyanogen

- A Los Angeles broker sold "comet insurance" at 25 cents per week, promising $500 to families of anyone killed by the comet

- Churches held all-night vigils; some people sealed their homes with rags and tape

On May 20, 1910, Earth passed through the tail. Nothing happened. The gas was far too diffuse — spread across millions of kilometers of space — to have any measurable effect on Earth's atmosphere.

1986: Scientific Triumph, Public Disappointment

The 1986 return was called "the worst pass of Halley's Comet in 2,000 years" for visual observers. The comet reached only magnitude +2.1 (barely visible to the naked eye), was best seen from the Southern Hemisphere, and was drowned out by urban light pollution for most city-dwellers. Millions who bought telescopes specifically for Halley were deeply disappointed.

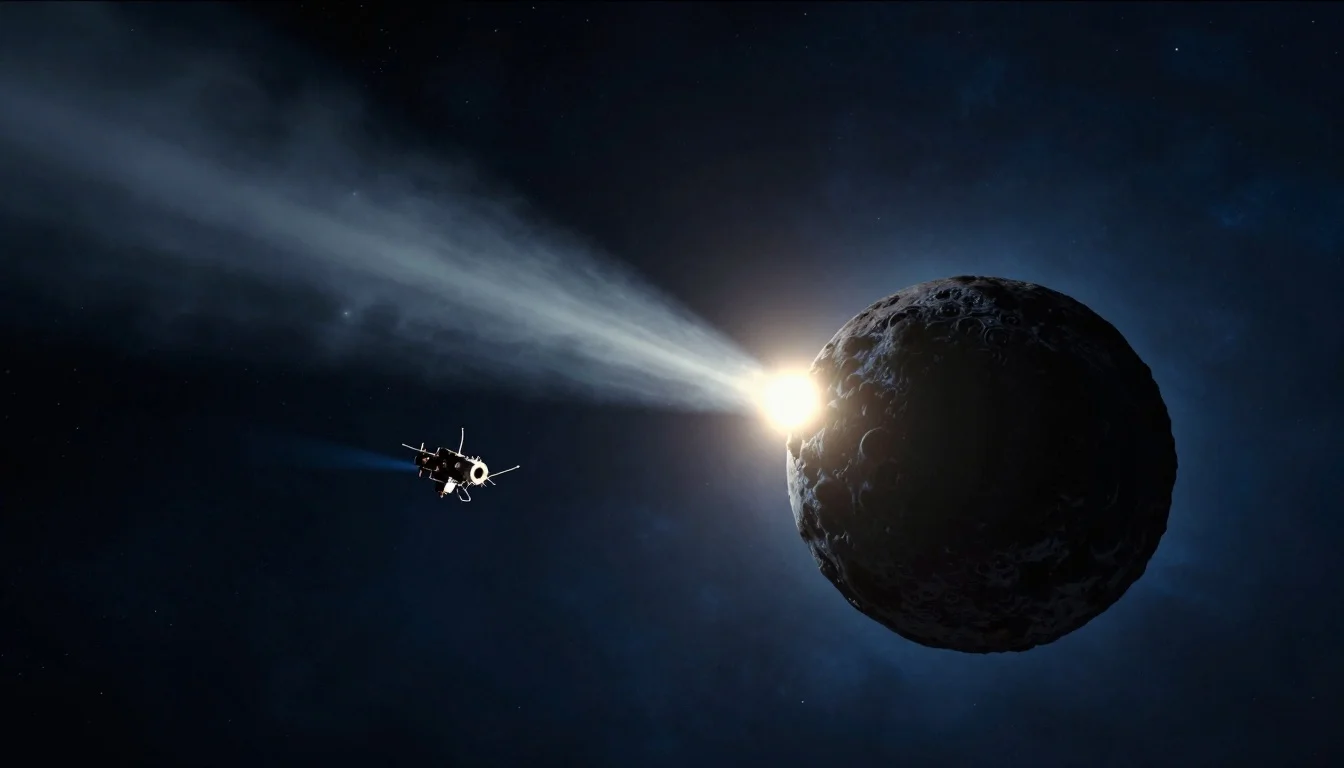

But scientifically, it was a revolution. An unprecedented "Halley Armada" of five spacecraft converged on the comet:

- Vega 1 & 2 (Soviet/French) — flew by at 8,000-8,900 km, capturing the first-ever images of a comet nucleus

- Suisei & Sakigake (Japan) — studied the hydrogen corona and solar wind interaction

- Giotto (ESA) — the crown jewel, passing just 596 km from the nucleus on March 14, 1986

Giotto revealed a nucleus that defied expectations: a dark, peanut-shaped body 15 km long and 8 km wide, with an albedo of just 0.03 — blacker than coal, making it one of the darkest objects in the solar system. Only 10-30% of the surface was active, with at least three jets erupting from the sunlit side. The rest was sealed under a dark, insulating crust.

The composition data was groundbreaking: 80% water vapor, 17% carbon monoxide, 3-4% carbon dioxide, plus the first detection of CHON particles (complex organic molecules containing carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen) in a comet.

What 2061 Will Look Like

The 2061 apparition will be dramatically better than 1986:

| Factor | 1986 | 2061 (predicted) |

|---|---|---|

| Peak magnitude | +2.1 (barely naked-eye) | -0.3 (brighter than Vega) |

| Relative brightness | Baseline | ~10x brighter |

| Earth-comet geometry | Opposite sides of Sun | Same side of Sun |

| Closest to Earth | 0.42 AU (poor geometry) | 0.477 AU (excellent geometry) |

| Visible tail | Short, hard to see | 10-15 degrees |

| Best hemisphere | Southern only | Both hemispheres |

At magnitude -0.3, Halley will be brighter than every star in the sky except Sirius and Canopus. It will be visible in twilight and from light-polluted cities. A study on forward-scattering brightness enhancement suggests that favorable geometry could make it even brighter than baseline predictions at certain viewing angles.

The viewing window runs from approximately May through September 2061:

- May-June: Pre-perihelion brightening as the comet approaches the Sun

- Late July: Perihelion and closest Earth approach within 24 hours of each other

- August 4-8: Likely the pinnacle — bright head with fully developed sweeping tail

- August-September: Post-perihelion with an expanding tail as the comet begins to recede

Halley's Meteor Showers: See Pieces of the Comet Every Year

You don't have to wait until 2061 to experience Halley's Comet. Every year, Earth passes through the debris stream Halley has left along its orbit, producing two major meteor showers:

Eta Aquariids (May)

- Active: April 15 – May 27

- Peak: May 5-6 (up to 50 meteors per hour)

- Best viewing: Pre-dawn hours; favors Southern Hemisphere

- Origin: Earth crosses Halley's outbound orbital path

The Eta Aquariids are one of the richest showers of the year. In 2026, the peak falls around May 5 at 03:51 UTC — though a waning gibbous Moon will interfere with fainter meteors.

Orionids (October)

- Active: September 26 – November 7

- Peak: October 21-22 (~20 meteors per hour)

- Best viewing: After midnight; both hemispheres

- Origin: Earth crosses Halley's inbound orbital path

- Characteristic: Fast meteors at ~66 km/s, often leaving persistent glowing trains

These showers occur regardless of where Halley itself is in its orbit — the debris has been spread along the entire orbital path over millennia of repeated passages.

Halley's Comet vs. 3I/ATLAS: Two Comets, Two Origins

The contrast between Halley's Comet and 3I/ATLAS could hardly be more striking. One is the most famous periodic comet in history, returning faithfully every 76 years. The other is a one-time visitor from another star, passing through our solar system never to return.

| Feature | 1P/Halley | 3I/ATLAS |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Our solar system (Oort Cloud) | Another star system |

| Orbit type | Closed ellipse (periodic) | Open hyperbola (one-time) |

| Eccentricity | 0.967 | 6.139 |

| Returns? | Every ~76 years | Never |

| Nucleus size | 15 × 8 km | ~1.3 km (2.6 km diameter) |

| Speed at perihelion | 54.55 km/s | 68 km/s |

| Interstellar speed | N/A (bound to Sun) | 58 km/s |

| Peak brightness | +2.1 (1986); -0.3 (2061) | ~magnitude 11.5 (never naked-eye) |

| Dominant volatile | Water (80% H₂O) | CO₂ (CO₂/H₂O ratio of 7.6) |

| Spacecraft visits | 5 (Halley Armada, 1986) | 0 |

| Meteor showers | Eta Aquariids + Orionids | None |

| Known appearances | 30+ since 240 BC | 1 |

What comparing them tells us:

Water is universal. Both Halley and 3I/ATLAS contain water ice, confirming that H₂O is a common building block of comets across different star systems.

Chemistry varies dramatically. Halley's coma is water-dominated (80% H₂O). 3I/ATLAS has one of the highest CO₂/H₂O ratios ever measured in any comet — 7.6, or 4.5 standard deviations above the trend for solar system comets. This suggests it formed near a CO₂ ice line in its home disk, in conditions quite different from where Halley was born.

Organics are everywhere. Both comets contain complex organic molecules — Halley's CHON particles (discovered by Giotto) and 3I/ATLAS's methane, methanol, and hydrogen cyanide (detected by JWST and SPHEREx). This suggests that the raw ingredients for prebiotic chemistry are commonplace across the galaxy.

Size matters. Halley's nucleus (15 × 8 km) is roughly 10 times larger than 3I/ATLAS (1.3 km radius). Yet 3I/ATLAS is still the largest interstellar object ever detected — about 40 times more massive than 2I/Borisov.

Missions to Meet Halley in 2061

Scientists are already planning for Halley's 2061 return — not just with ground telescopes, but with a potential Rosetta-style rendezvous mission.

HCREM: Halley Comet Rendezvous Mission

Published in Planetary and Space Science in February 2025, this detailed mission concept proposes:

- Launch: Late 2030s (targeting ~2036)

- Trajectory: Direct transfer from Earth, then a Jupiter gravity assist to match Halley's retrograde orbit

- Propulsion: Solar electric propulsion for trajectory correction; radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) for power beyond Saturn

- Rendezvous: Achieves zero relative velocity with the comet beyond Saturn's orbit (~2056), when Halley is still frozen and inert

- Science phase: Accompanies Halley from beyond Saturn, through perihelion in July 2061, and outward again — watching the comet "wake up" in real time

This would be transformative: observing the onset of sublimation of super-volatile species (CO, CO₂) before water-ice activation, monitoring how activity evolves with heliocentric distance, and capturing high-resolution images of the nucleus surface as it transitions from dormancy to full activity.

ESA Comet Interceptor (2029)

While not targeting Halley specifically, ESA's Comet Interceptor — launching in 2029 — will park at the L2 Lagrange point and wait for a suitable long-period or interstellar comet to intercept. The technology and science from this mission will directly inform any future Halley rendezvous. Together, the two missions would provide an unprecedented comparison between a pristine "new" comet and the most-studied periodic comet in history.

The Countdown

Halley's Comet has watched over human history for at least 2,266 years — from the first Chinese records in 240 BC through the Bayeux Tapestry, the cyanogen panic, and the Giotto encounter. It will return in 2061 with the best viewing geometry in over a century.

In the meantime, 3I/ATLAS has given us something Halley never could: a direct chemical sample from another star's planetary system. Together, these two comets — one a faithful periodic visitor, the other a once-in-a-civilization interstellar guest — are rewriting our understanding of what comets are made of and where the building blocks of planets come from.

The next Eta Aquariid meteor shower peaks on May 5-6, 2026. Step outside before dawn, look toward the constellation Aquarius, and watch pieces of Halley's Comet burn through Earth's atmosphere at 66 km/s. It's the closest any of us will get to Halley for another 35 years.

Compare Halley's orbit to 3I/ATLAS on our Orbit page, explore the full timeline of 3I/ATLAS discoveries, and learn about the science of interstellar comets.