What Direction Does a Comet's Tail Always Point?

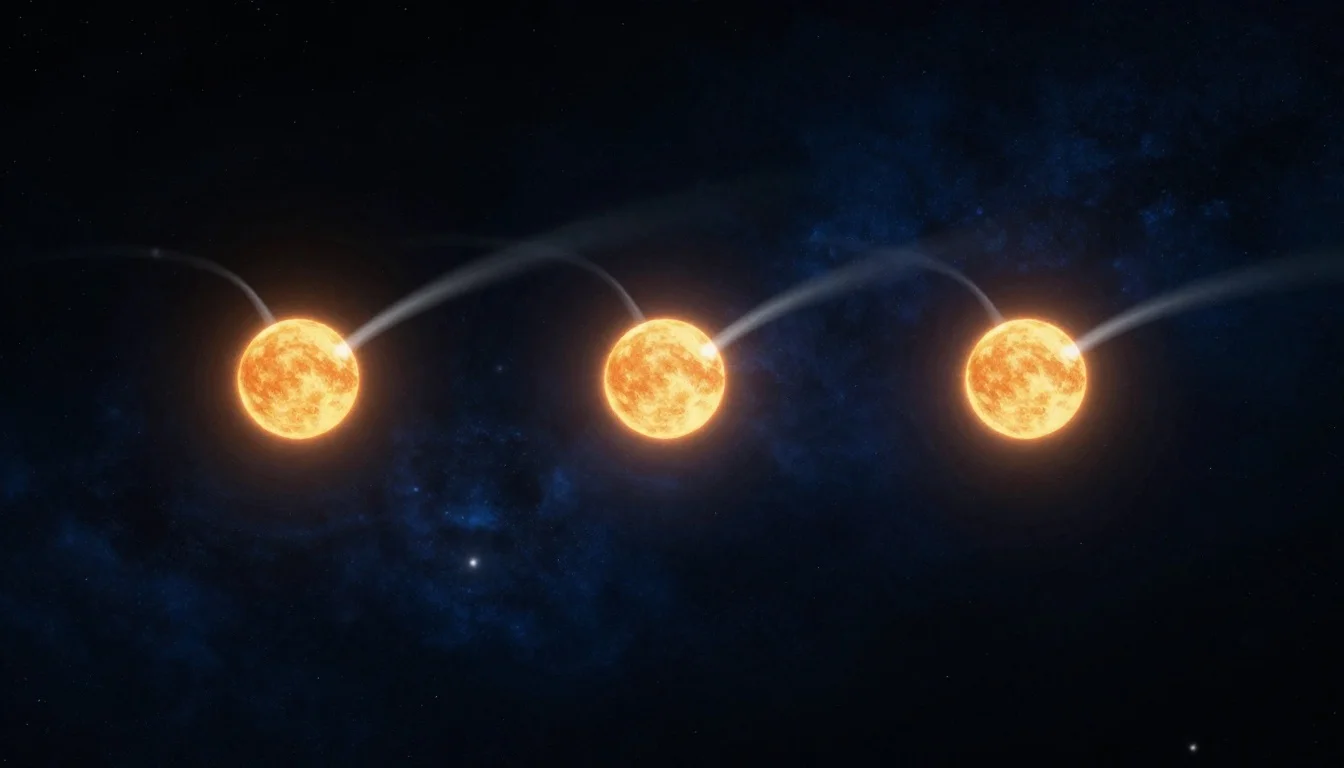

A comet's tail always points away from the Sun. It doesn't trail behind the comet like exhaust from a rocket — it is pushed outward by forces radiating from our star. This means a comet's tail actually leads it as it travels away from the Sun after perihelion. Understanding why reveals some of the most elegant physics in our solar system.

The Golden Rule: Always Away from the Sun

No matter where a comet is in its orbit — approaching the Sun, rounding perihelion, or heading back out toward deep space — its tail points away from the Sun. This is one of the most reliable rules in cometary science.

As a comet approaches the Sun, its tail streams behind it, much as you might expect. But after perihelion, something counterintuitive happens: the tail swings around and leads the comet as it moves outward. The comet essentially flies tail-first away from the Sun.

This behavior was first documented centuries ago by observers who noticed that comet tails didn't simply trail behind the nucleus. The Chinese astronomer records from as early as the 7th century noted this peculiar orientation. It wasn't until the 19th and 20th centuries that physicists understood the forces responsible.

Two Tails, Two Forces

Most active comets develop not one but two distinct tails, each driven by a different solar force and pointing in slightly different directions:

The Ion (Gas) Tail

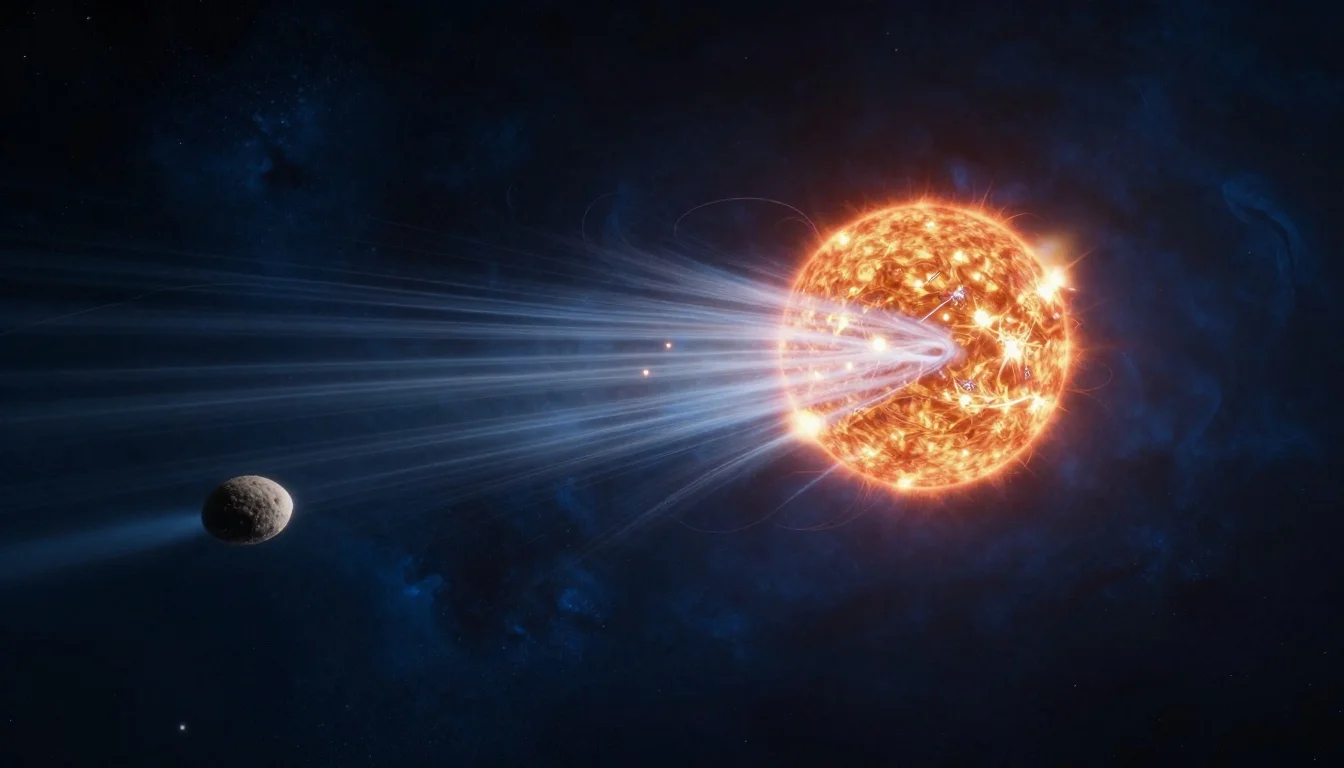

The ion tail (also called the plasma tail or gas tail) is composed of molecules from the comet's coma that have been ionized — stripped of electrons — by the Sun's ultraviolet radiation. These charged particles are caught by the solar wind, a stream of charged particles flowing outward from the Sun at roughly 400–800 km/s.

The solar wind's embedded magnetic field sweeps these ions into a narrow, straight tail that points almost exactly in the anti-solar direction — directly away from the Sun. The ion tail often appears bluish due to the fluorescence of carbon monoxide ions (CO⁺).

The Dust Tail

The dust tail consists of tiny solid particles — roughly the size of smoke particles — liberated from the nucleus as ices sublimate. These grains are pushed away from the Sun by radiation pressure: the physical force exerted by sunlight itself.

Because dust particles are heavier than ions, radiation pressure accelerates them more slowly than the solar wind pushes ions. The grains also retain some of the comet's orbital velocity. The result is a broad, gently curved tail that fans out from the coma. It appears whitish-yellow because the particles reflect sunlight rather than fluorescing.

While both tails point generally away from the Sun, the dust tail curves noticeably toward the comet's orbital path, while the ion tail remains ruler-straight.

Why the Sun Wins: Solar Wind and Radiation Pressure

Two forces conspire to aim comet tails away from the Sun:

1. Solar radiation pressure — Photons carry momentum. When sunlight strikes a small dust grain, each absorbed or reflected photon imparts a tiny push. For particles smaller than about 1 micron, this outward push exceeds the Sun's gravitational pull, driving grains into the dust tail. The ratio of radiation pressure to gravity is called beta (β): particles with β > 1 are pushed outward, while those with β < 1 remain more gravitationally bound and lag behind in the comet's orbit.

2. Solar wind — The Sun continuously emits a wind of protons, electrons, and alpha particles at hundreds of kilometers per second. This magnetized plasma interacts directly with ions in the comet's coma, accelerating them to speeds of tens to hundreds of km/s away from the Sun. The ion tail can respond to changes in solar wind conditions within minutes, sometimes producing dramatic disconnection events where the tail appears to break off and reform.

Together, these forces ensure that cometary material is always being pushed outward from the Sun — regardless of which direction the comet itself is traveling.

The Exception That Proves the Rule: Anti-Tails

Occasionally, a comet appears to sprout a spike pointing toward the Sun — an apparent violation of the golden rule. This feature is called an anti-tail, and it's almost always a geometric illusion.

Here's how it works:

- Large dust particles (heavier than those in the normal dust tail) are less affected by radiation pressure. They drift slowly and remain concentrated near the comet's orbital plane, forming a broad, flat sheet of debris.

- When Earth crosses the comet's orbital plane, we view that sheet edge-on. The foreshortened perspective compresses it into what looks like a narrow spike pointing sunward.

The anti-tail typically lasts only a few days around the plane-crossing date. Notable examples include Comet Hale-Bopp in 1997, Comet Lulin in 2009, C/2023 A3 Tsuchinshan–ATLAS in 2024, and most recently C/2025 R2 SWAN in late 2025.

You can read more about R2 SWAN's anti-tail in our dedicated article.

Famous Comet Tails Through History

Some of the most awe-inspiring sights in astronomical history have been comet tails stretching across the sky:

-

Halley's Comet (1P/Halley) — The most famous periodic comet, recorded as far back as 240 BC. During its 1910 apparition, Earth actually passed through its tail, sparking public alarm (and brisk sales of "comet pills"). Its dust and ion tails were both prominently visible. It returns next around 2061 — explore the timeline on our Halley's Comet page.

-

Comet Hale-Bopp (C/1995 O1) — Visible to the naked eye for a record-breaking 18 months in 1996–1997. Its dust tail stretched 40–45 degrees across the sky, and it clearly displayed both a white dust tail and a blue ion tail simultaneously. Hale-Bopp also revealed a rare sodium tail, a third tail type driven by radiation pressure on neutral sodium atoms.

-

Comet Hyakutake (C/1996 B2) — Although it appeared just a year before Hale-Bopp, Hyakutake holds the record for the longest measured comet tail: over 570 million km (3.8 AU), discovered by the Ulysses spacecraft.

-

Comet NEOWISE (C/2020 F3) — The standout comet of 2020. Its dust and ion tails stretched over 50 degrees at peak, offering millions of lockdown-era skywatchers a spectacular show.

Each of these comets obeyed the same fundamental rule: tails pointed away from the Sun, shaped by solar radiation and wind.

3I/ATLAS: An Interstellar Twist on the Rule

The arrival of 3I/ATLAS — the third confirmed interstellar object — in 2025 added a fascinating new chapter to our understanding of comet tails.

During July and August 2025, 3I/ATLAS displayed a prominent feature extending toward the Sun. Unlike a classical anti-tail (which is a geometric illusion), this sunward feature appeared to be a tightly collimated jet of material being ejected from the comet's sunlit hemisphere. Researchers identified jet structures that changed direction on a repeating cycle of roughly 7 hours and 45 minutes, consistent with the rotation of the nucleus.

The rotation axis of 3I/ATLAS was aligned to within just 8 degrees of the sunward direction — an orientation with an extremely low probability of occurring by chance. By late August 2025, as the comet approached perihelion, the sunward feature faded and a conventional anti-solar tail developed, restoring the familiar pattern.

Whether 3I/ATLAS's sunward jet represents a genuinely novel phenomenon or an extreme version of known cometary activity remains an active area of research. You can track its position and tail orientation in real time using our interactive 3D orbit viewer, and follow the latest findings on our science page.

See It for Yourself

The next time a bright comet graces our skies, you can verify the golden rule with your own eyes. Here's how:

- Locate the Sun's position — even after sunset, note where the Sun dipped below the horizon. The comet's tail will point away from that direction.

- Use binoculars — even modest 10×50 binoculars will reveal tail structure that's invisible to the unaided eye, including the separation between the dust and ion tails.

- Photograph it — a DSLR or mirrorless camera on a tripod with exposures of 2–10 seconds can capture vivid tail detail. Stacking multiple exposures brings out the faint outer tail.

- Compare over several nights — as the comet moves along its orbit and the Earth–Sun–comet geometry shifts, you'll see the tail direction change relative to the stars, but it will always point away from the Sun.

For detailed guidance on equipment, settings, and finding comets, visit our observing guide. To see when the next bright comet will be visible, check our timeline of upcoming events.

The simple rule — a comet's tail always points away from the Sun — connects backyard stargazing to some of the deepest physics of our solar system: radiation pressure, magnetohydrodynamics, and the relentless outflow of the solar wind. It's a reminder that even the most beautiful celestial sights have elegant explanations, waiting for anyone curious enough to ask why.