The Asteroid Belt: What Separates Inner and Outer Planets

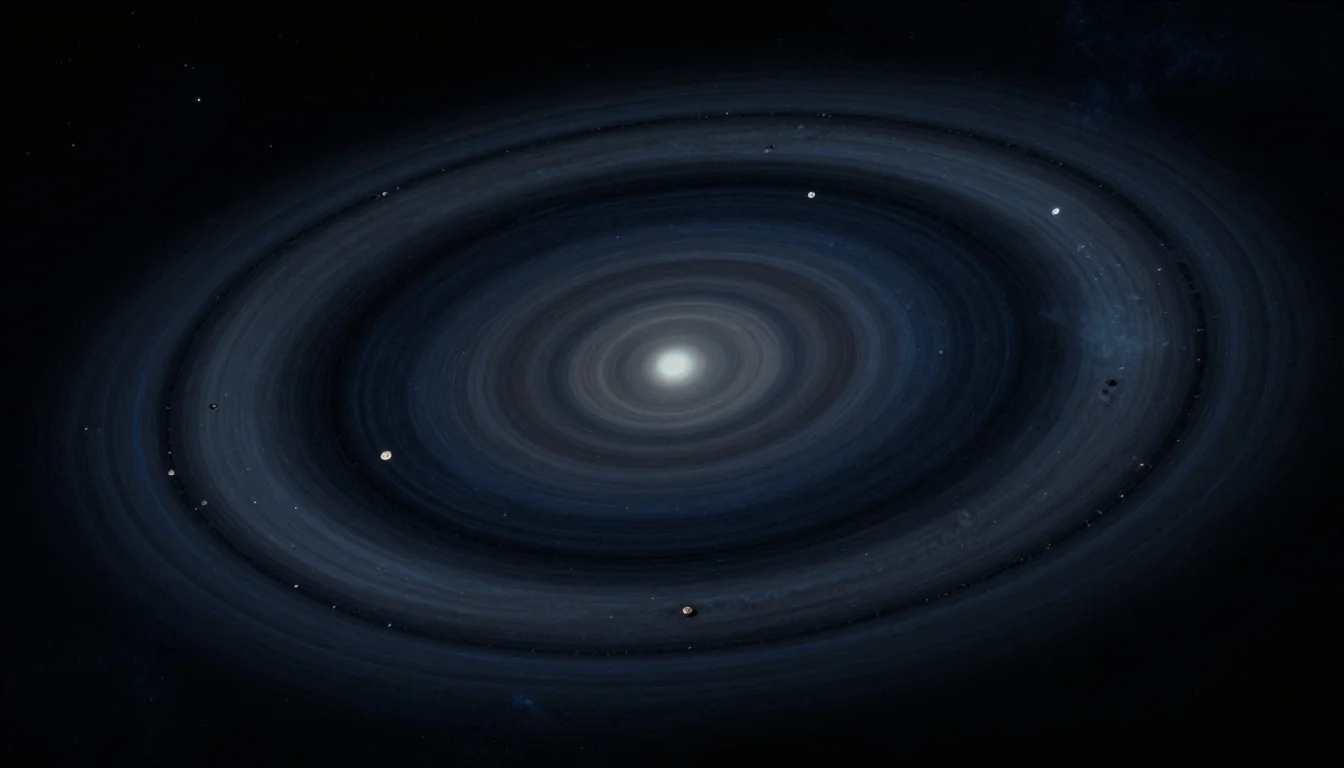

The asteroid belt — a vast ring of rocky debris orbiting the Sun between Mars and Jupiter — is the natural boundary that separates the solar system's small, rocky inner planets from the enormous gas and ice giants of the outer solar system. But this boundary is far more than a dividing line on a diagram. It tells the story of a planet that never formed, a giant planet's gravitational reach, and the fundamental physics that shaped every world we know.

Where Is the Asteroid Belt?

The asteroid belt occupies a torus-shaped region of space between approximately 2.2 and 3.2 AU from the Sun (1 AU = the Earth–Sun distance, about 150 million km). That places it squarely between the orbit of Mars (at ~1.5 AU) and Jupiter (at ~5.2 AU).

Despite what science-fiction movies suggest, the belt is overwhelmingly empty space. The average distance between individual asteroids is roughly 960,000 km — about 2.5 times the distance from Earth to the Moon. A spacecraft passing through the belt has a negligible chance of hitting anything; NASA's Juno, Pioneer, and Voyager missions all transited it without incident.

The belt contains millions of objects ranging from dust-sized grains to the dwarf planet Ceres (950 km across), yet the total mass of the entire belt is only about 3% of the Moon's mass — roughly 2.4 × 10²¹ kg. If you could gather every asteroid into a single body, it would be far smaller than our Moon.

The Inner Planets: Rocky and Compact

Sunward of the asteroid belt lie the four terrestrial (inner) planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars. They share a set of defining characteristics:

- Rocky composition — Made primarily of silicate rock and iron-nickel metal. They have solid surfaces you could stand on.

- Small size — Earth, the largest, is just 12,742 km in diameter. Mercury, the smallest, is only 4,880 km across.

- Thin or no atmospheres — Mercury has virtually no atmosphere; Mars has a thin CO₂ envelope. Venus is the exception with its dense, crushing atmosphere, but even it is dwarfed by a gas giant's bulk.

- Few or no moons — Mercury and Venus have none; Earth has one; Mars has two tiny captured asteroids (Phobos and Deimos).

- No ring systems — None of the terrestrial planets possess rings.

These planets formed in the hot inner region of the protoplanetary disk, where temperatures were too high for volatile compounds like water ice, methane, and ammonia to condense. Only refractory materials — rock and metal — could survive, limiting the raw material available for planet-building.

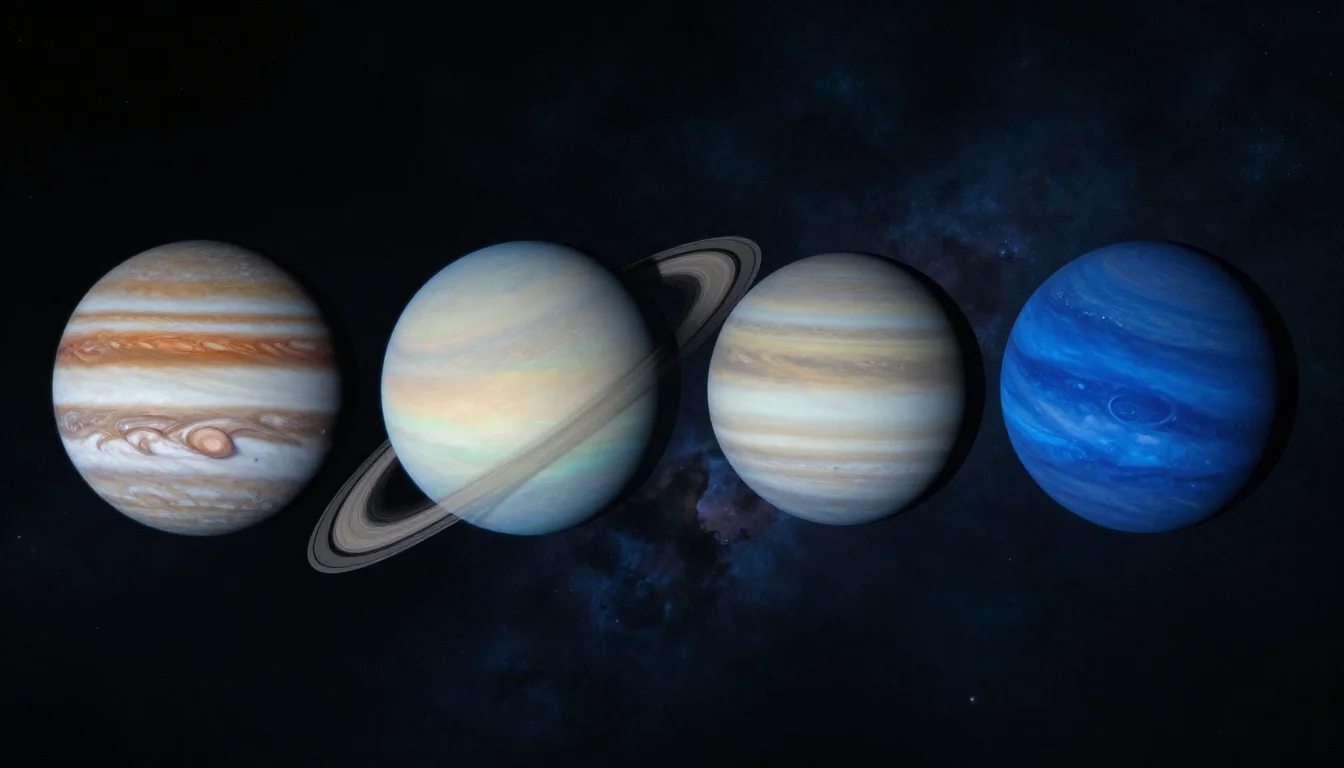

The Outer Planets: Gas and Ice Giants

Beyond the asteroid belt orbit the four Jovian (outer) planets: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. They are fundamentally different from the inner worlds:

- Massive size — Jupiter alone contains more mass than all other planets combined. Its diameter is 11 times Earth's.

- Gas and ice composition — Jupiter and Saturn are gas giants, composed predominantly of hydrogen and helium. Uranus and Neptune are ice giants, with large fractions of water, ammonia, and methane ices in their interiors.

- No solid surface — These planets have no well-defined boundary between atmosphere and interior. Pressure simply increases with depth until gases become liquid, then metallic.

- Extensive moon systems — Jupiter has 95 known moons; Saturn has 146. Even Uranus and Neptune have dozens each.

- Ring systems — All four outer planets possess rings, though Saturn's are by far the most spectacular.

- Strong magnetic fields — Generated by convection in their deep metallic hydrogen (Jupiter, Saturn) or ionic water (Uranus, Neptune) interiors.

These giants formed beyond the frost line (also called the snow line), located at roughly 2.7 AU during the solar system's formation. Beyond this distance, temperatures in the protoplanetary disk dropped low enough for water ice to condense, dramatically increasing the amount of solid material available. The resulting ice-rich cores grew massive enough to gravitationally capture enormous envelopes of hydrogen and helium gas from the surrounding disk.

Why the Belt Exists: The Planet That Never Formed

The asteroid belt isn't the wreckage of a destroyed planet — it's the remains of a planet that never came together in the first place.

During the solar system's formation ~4.6 billion years ago, planetesimals in the region between Mars and Jupiter were on track to accrete into a fifth terrestrial planet. But Jupiter, which formed first and fastest among the planets, had other plans. Its immense gravity stirred up the orbits of these rocky building blocks, increasing their relative velocities so dramatically that collisions became destructive rather than constructive.

Instead of gently merging, planetesimals smashed apart. The would-be planet was shattered before it could fully assemble. Over billions of years, continued gravitational perturbations from Jupiter (and to a lesser extent, Saturn) have further depleted the belt's mass. The original belt may have contained enough material to form an Earth-mass planet, but today less than 0.1% of that mass remains.

This is why the asteroid belt marks such a clean dividing line: Jupiter's gravity not only prevented a planet from forming in this zone but also established the boundary between two fundamentally different regimes of planet formation — rocky worlds inside the frost line and giant worlds outside it.

Kirkwood Gaps: Jupiter's Gravitational Fingerprint

Jupiter's influence on the asteroid belt goes beyond simply preventing planet formation. It has carved distinct gaps in the distribution of asteroid orbits, first identified by American astronomer Daniel Kirkwood in 1866.

These Kirkwood gaps occur at specific orbital distances where an asteroid's orbital period forms a simple ratio with Jupiter's:

| Resonance | Orbital ratio | Distance (AU) |

|---|---|---|

| 4:1 | 4 asteroid orbits per 1 Jupiter orbit | 2.06 |

| 3:1 | 3 per 1 | 2.50 |

| 5:2 | 5 per 2 | 2.82 |

| 7:3 | 7 per 3 | 2.95 |

| 2:1 | 2 per 1 | 3.28 |

At these resonance points, Jupiter's gravitational tugs accumulate over millions of years, gradually nudging asteroids into more eccentric orbits until they either collide with a planet, plunge into the Sun, or are ejected from the solar system entirely. The result is a series of clearly defined gaps — empty lanes in an otherwise populated region.

The Kirkwood gaps are one of the most elegant demonstrations of orbital resonance in the solar system, and they provide direct, observable evidence of how Jupiter shaped (and continues to shape) the architecture of the belt.

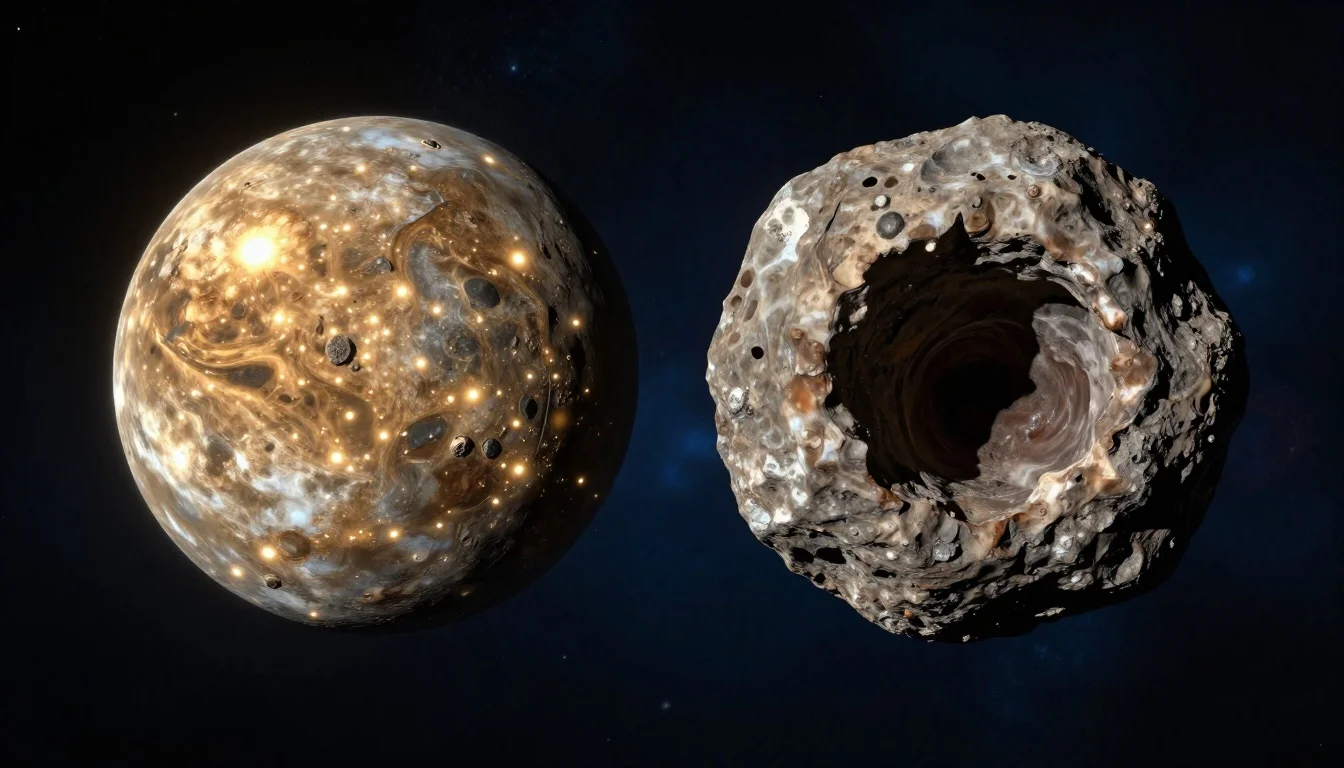

The Belt's Biggest Residents: Ceres and Vesta

While most asteroids are modest chunks of rock, the belt contains two truly remarkable worlds:

Ceres

Ceres is the largest object in the asteroid belt and the only one massive enough to be classified as a dwarf planet. At 950 km in diameter, it accounts for roughly 39% of the belt's entire mass. NASA's Dawn spacecraft orbited Ceres from 2015 to 2018 and discovered bright spots in Occator Crater — deposits of sodium carbonate likely brought to the surface by cryovolcanic activity. Ceres may harbor a subsurface ocean of briny water, making it a target of astrobiological interest.

Vesta

Vesta is the second-largest asteroid, with a mean diameter of about 525 km. It is one of the brightest objects in the belt and occasionally visible to the naked eye from Earth. Vesta's most dramatic feature is Rheasilvia, a colossal impact basin 505 km across at its south pole — nearly as wide as Vesta itself. Dawn also visited Vesta (2011–2012), revealing a differentiated interior with an iron core, mantle, and crust — essentially a miniature terrestrial planet.

Together with Pallas and Hygiea, these four largest objects contain roughly 60% of the belt's total mass. Everything else is spread across millions of smaller fragments.

3I/ATLAS: An Interstellar Visitor Crossing the Belt

The asteroid belt recently played host to an extraordinary traveler. 3I/ATLAS — the third confirmed interstellar object ever detected — crossed through the belt on its hyperbolic trajectory through our solar system.

3I/ATLAS's path is remarkable for several reasons:

- Its orbit is inclined only about 5 degrees from the ecliptic plane — a rare alignment (roughly 0.2% probability) that brought it through the heart of the belt rather than passing above or below it.

- On 19 December 2025, 3I/ATLAS passed 1.798 AU from Earth while inside the asteroid belt, beyond the 4:1 Kirkwood gap.

- With an orbital eccentricity of 6.14 — far greater than 1I/'Oumuamua (1.2) or 2I/Borisov (3.4) — it is moving far too fast to be captured by the Sun's gravity and will exit the solar system entirely.

Despite passing through the belt, the vast spacing between asteroids meant there was essentially zero risk of collision. But the interstellar comet's transit through this boundary zone — the same region that divides our inner and outer planets — underscored the belt's role as a crossroads within the solar system.

You can watch 3I/ATLAS's trajectory through the asteroid belt region in our interactive 3D orbit viewer, and follow the latest observations on our news page.

The asteroid belt is far more than a line on a diagram separating "inner" from "outer." It is a fossil record of the solar system's violent youth, a testament to Jupiter's gravitational dominance, and a reminder that the architecture of our planetary neighborhood was anything but inevitable. Every gap, every shattered fragment, and every visiting comet adds a new page to that story — one we're still reading today. Explore more about the solar system's structure on our science page.